Drawn by the allure of untamed peaks and the thrill of technical mountaineering, an Indo-British expedition ventured into the Kumaon region of the Indian Himalaya during the summer of 1992. This rugged terrain, sculpted by nature’s relentless hand, served as a magnet for those seeking an unforgettable alpine odyssey.

Kuman

Nestled in the western foothills of the Himalayas Kumaon comprises three distinct valleys each offering a unique blend of natural splendor and mountaineering challenges. The easternmost valley known as Darma Ganga is home to an array of towering peaks that soar above 6,000 meters. To the west lies the Pindari Valley, a realm of captivating beauty and formidable 6,000-meter summits, including the majestic Panwali Dwar (6,663 meters) and Nanda Khat (6,611 meters). Branching off from Pindari Valley, the Sunderhunga Valley gracefully weaves its way towards the southern edge of the Nanda Devi Sanctuary, a haven for mountaineering enthusiasts. At the heart of Kumaon lies the Milam Glacier Valley, renowned for its awe-inspiring Kalabaland Glacier. Southeast of the Milam Glacier, the Panch Chuli group stands sentinel, its five peaks piercing the Himalayan sky.

Panch Chuli Massif

Nestled between the majestic Nanda Devi in Garhwal and the towering Api in Nepal, the Panch Chuli massif stands as a testament to nature’s grandeur. To reach this Himalayan gem, mountaineers can embark on an exhilarating journey through the Sona and Meola Glaciers, approaching from the east.

The massif comprises five awe-inspiring peaks, each with its own unique personality. Panch Chuli I, standing tall at 6,355 meters, marks the northwestern sentinel of the group. Next in line is Panch Chuli II, the towering monarch, reaching an impressive height of 6,904 meters. Panch Chuli III, Panch Chuli IV, and Panch Chuli V, with their respective elevations of 6,312 meters, 6,334 meters, and 6,437 meters, complete the royal family of peaks.

Beyond these five giants, the Panch Chuli massif boasts an entourage of equally captivating peaks, including Rajrambha (6,537 meters), Nagalaphu (6,410 meters), Shadev (5,782 meters), Telkot (6,102 meters), Bainti (6,071 meters), and Nagling (6,041 meters). Each peak adds its own distinctive character to the massif’s breathtaking landscape.

The Panch Chuli peaks hold a special place in the hearts of local people, who have long revered them as sacred. The massif’s name derives from the legendary Pandava brothers, Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva, central characters in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. According to local folklore, these five brothers cooked their last meal on the five peaks before ascending to heaven.

At sunrise, a magical spectacle unfolds as the peaks reflect the sun’s rays, casting a hearth-like glow upon the surrounding landscape. This celestial dance repeats shortly after sunset, illuminating the path towards Nirvana, the ultimate state of spiritual bliss. The Panch Chuli peaks thus serve as a beacon of inspiration and spiritual enlightenment for all who behold their splendor.

Read More: Everest Disaster 1996 | Tragedy on Top of the World

East Attempts

Before embarking on his two Mount Everest expeditions in 1933 and 1936, renowned English mountaineer Hugh Ruttledge ventured into the Kumaon region of India in 1929 to explore the Panch Chuli peaks. Approaching the massif from the east, Ruttledge meticulously examined potential climbing routes, leading him to believe that the sharp ridge of the north arete might be conquerable. However, despite his assessment, no one would successfully summit any of the Panch Chuli peaks for decades to come.

In 1950, A Scottish expedition led by W. H. Murray attempted an ascent from the east, aiming to reach the north col and follow the northeast ridge. However, the challenging terrain proved insurmountable, hindering their progress and forcing them to abandon their attempt.

Undeterred by previous setbacks, British climber Kenneth Snelson and South African J. de V. Graaff set their sights on the northeast summit ridge of the massif in the same season, just 20 days after the Scottish expedition’s retreat. However, their path was blocked by towering cliffs, prompting them to consider the south ridge as an alternative. Unfortunately, their efforts were thwarted once again, and they were forced to abandon their attempt on the southeast face after just 122 meters.

Throughout the years, the Panch Chuli peaks continued to challenge mountaineering enthusiasts from around the globe. In 1970 and 1988, two additional expeditions originating from the east of the massif were met with failure, further solidifying the reputation of these peaks as formidable adversaries.

Despite these early setbacks, the allure of the Panch Chuli peaks remained undiminished, attracting mountaineers eager to test their skills and conquer the seemingly impregnable summits.

Read More: Sleeping Beauty Mount Everest Dead Bodies

West Attempts

In 1951, just a year after Murray’s expedition, Austrian mountaineers Heinrich Harrer and Frank Thomas, accompanied by two Sherpas and a botanist, embarked on a groundbreaking adventure. They approached the Panch Chuli massif via the Uttari Balati Glacier, skillfully maneuvering around three formidable icefalls. Their pioneering expedition marked a significant step forward in understanding the massif’s terrain and potential climbing routes.

Upon reaching the Balati Plateau, Harrer carefully examined both the north and west ridges, ultimately deciding to attempt the west ridge. However, their ascent was cut short when one of the Sherpas suffered a severe fall and injury. Despite this setback, their 16-day expedition provided invaluable insights for future mountaineers, paving the way for subsequent attempts.

The following year, the Panch Chuli peaks witnessed a surge of activity, with two different parties reaching the Balati Plateau from the west. In 1953, Indian mountaineer P. N. Nikore boldly claimed to have successfully summited Panch Chuli II alone, but his assertion lacked any supporting evidence.

Over a decade later, another Indian expedition emerged, led by Captain AK Chowdhury. Their ambitious goal was to conquer Panch Chuli II, the highest peak in the massif. They subsequently claimed to have ascended Panch Chuli III, IV, and V within a mere two days. However, their claim raised skepticism among mountaineering circles, as these peaks were deemed inaccessible from the Balati Plateau. Further investigation revealed that they had mistakenly ascended three humps near Panch Chuli II rather than the actual peaks.

First Ascents

After years of failed attempts and relentless determination, the Panch Chuli peaks finally began to yield to the intrepid spirit of mountaineers. In 1972, a momentous breakthrough occurred when an Indian expedition led by Hukam Singh successfully summited 6,355m Panch Chuli I, marking the first ascent of any peak within the massif.

Their triumph was achieved by following the Balati Plateau route pioneered by Heinrich Harrer in 1951. This route, with its treacherous icefalls and challenging terrain, had previously deterred climbers. However, the Indian team’s perseverance paid off, and they proudly planted their flag on the summit.

Inspired by this success, another Indian team, led by Mahendra Singh, set their sights on conquering the highest peak in the massif, 6,904m Panch Chuli II. In 1973, after meticulously fixing nearly 3,000 meters of rope along the southwest ridge, their 18-member team triumphantly reached the summit on May 26.

While Panch Chuli III remains elusive, defying all attempts to conquer its summit, Panch Chuli IV finally yielded to mountaineering prowess in 1995. A New Zealand expedition led by John Nankervis successfully ascended this challenging peak, marking another milestone in the history of Panch Chuli conquests.

Indo-British The 1992 Panch Chuli Expedition

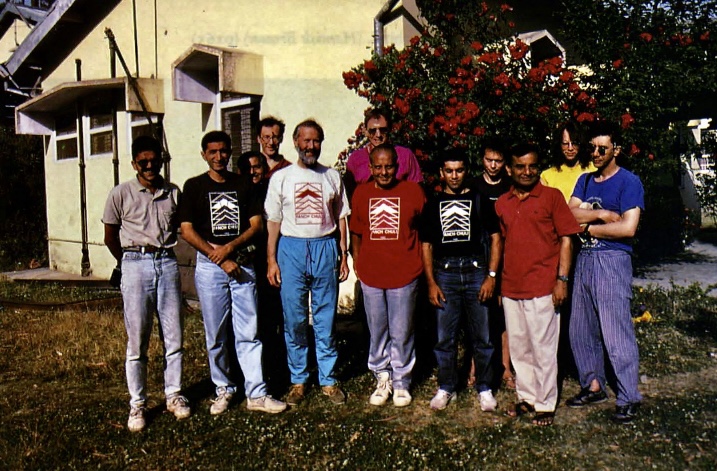

In May 1992, a dream team of mountaineers from India and the United Kingdom embarked on an ambitious expedition to the formidable Panch Chuli peaks in the Indian Himalayas. This joint venture led by renowned mountaineers Harish Kapadia and Chris Bonington marked the third collaboration between these two nations showcasing their shared passion for conquering the world’s highest peaks.

The expedition team comprised a diverse group of individuals each bringing their unique skills and experience to the challenge. Harish Kapadia a legendary Indian mountaineer had already achieved over 20 first ascents while Chris Bonington a British mountaineering icon was renowned for his high-level first ascents and groundbreaking new routes.

Among the other notable members were Victor Saunders, a hesitant architect turned exceptional mountaineer, known for his humorous accounts of his climbs, and Stephen Venables, a mountaineering pioneer who had successfully summited Everest without supplemental oxygen via a new route.

On May 10, 1992, the expedition team set off from Bombay, accompanied by 84 porters carrying their gear. Following the Uttari Balati Glacier, they established their base camp at an altitude of 3,270 meters below the snout of the glacier. This base camp, one of the lowest in the Himalayas, marked the starting point of their ascent.

The height difference between the base camp and Panch Chuli II, the highest peak in the massif, was a staggering 3,700 meters, surpassing the elevation gain of even Mount Everest. This daunting vertical challenge only fueled the determination of the mountaineers, who were eager to test their skills against the towering peaks.

As they embarked on their ascent, the team faced a series of obstacles, from treacherous icefalls to unpredictable weather conditions. Yet, their collective experience, resilience, and shared passion for mountaineering prevailed. They worked together seamlessly, supporting and motivating each other through every challenge.

After weeks of relentless effort, the expedition team achieved remarkable success. They summited several peaks within the massif, including Panch Chuli II, III, and IV. Each ascent was a testament to their physical prowess, technical expertise, and unwavering determination.

The joint Indo-British expedition to the Panch Chuli peaks stands as a testament to the power of collaboration and the indomitable spirit of mountaineers. It was a remarkable achievement that showcased the combined strength of two nations and their shared passion for conquering the world’s most challenging peaks.

From Victor’s Terror to Harish’s Horror

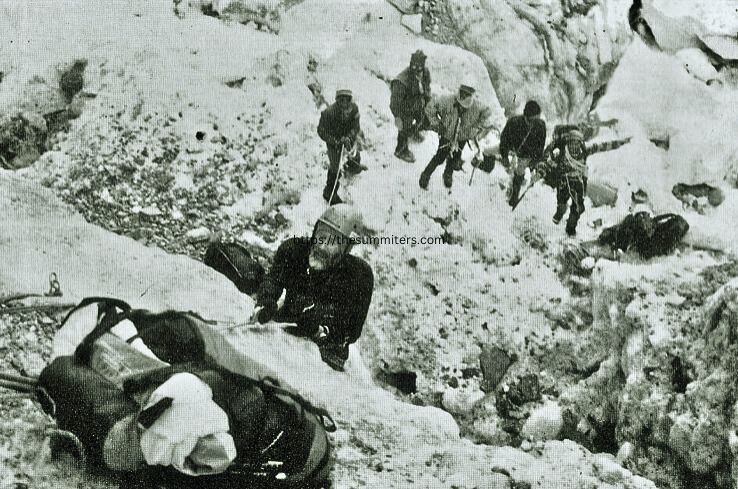

After establishing their base camp, the expedition team diligently progressed towards their goal, setting up a glacier camp above the first icefall at an altitude of 3,900 meters. However, the terrain grew increasingly difficult, posing new challenges for the mountaineers.

Two particularly dangerous icefalls still lay ahead, demanding careful navigation and technical expertise. Victor Saunders, a skilled mountaineer, took on the task of leading the way through the treacherous left side of the glacier. This section, aptly named “Victor’s Terror,” reflected the daunting nature of the terrain.

As Saunders diligently worked his way through the icefall, a sudden loud crash broke the silence. Bonington, who had been secured by a jumar on the fixed rope, found himself hanging precariously in mid-air. The ground beneath him had collapsed, leaving him suspended in a precarious situation.

Fortunately, Harish Kapadia, drawing upon his extensive mountaineering experience, identified an alternative route through the icefalls, this time on the right side of the glacier. This path, aptly named “Harish’s Horror,” was no less challenging, but it offered a viable way to bypass the second icefall.

The expedition team’s perseverance paid off, and they successfully navigated the treacherous terrain, reaching their advanced base camp on May 26. Located at an altitude of 4,840 meters below a small rock buttress, this camp served as their final staging point before attempting to summit the Panch Chuli peaks.

Not Content With one New Route

Despite the challenges they faced, the expedition team remained undeterred. From their advanced base camp, they split into smaller groups to explore and attempt new routes on the surrounding peaks.

On May 28, Chris Bonington and Graham Little made the first ascent of 5,750-meter Sahadev East via the northwest snow rib. Their success marked a significant achievement for the expedition.

However, on June 4, misfortune struck the team when Indian climber Vijay Kothari slipped while descending the treacherous “Harish’s Horror” gully. He fell rapidly towards a massive bergschrund at the bottom. Fortunately, fellow team member Sundersinh reacted swiftly and managed to catch Kothari just in time to prevent a catastrophic fall. Although Kothari’s ankle was broken, two Indian climbers carried him safely back to the glacier camp, where he was evacuated by helicopter to a hospital for treatment.

Undeterred by this setback, the expedition continued to push their limits. On June 5, a team of Richard Renshaw, Victor Saunders, Stephen Sustad, and Stephen Venables achieved a remarkable feat, conquering the 6,537-meter peak of Rajrambha via a newly discovered route. Their ascent involved traversing the east ridge and summiting 6,000-meter Menaka Peak, marking the first ascent of this peak. They then descended via the west ridge and south face, completing a challenging and rewarding circuit.

Just two days later, on June 7, Muslim Contractor, Monesh Devjani, and Pasang Bodh successfully summited Panch Chuli II for the fourth time. This ascent further cemented the expedition’s achievements in the region.

On June 8, Bonington and Little continued their quest for new routes, successfully opening a new path on Panch Chuli II via the west spur. Their determination and skill were evident in their ability to chart a new course on this challenging peak.

On June 20, Harish Kapadia, Contractor, Devjani, Kubram, and Prakash Chand made history by achieving the first ascents of 5,220-meter Panchali Chuli and 5,250-meter Draupadi via the Panchali Glacier. Their success added two more peaks to the expedition’s impressive tally.

Despite facing setbacks like Kothari’s accident, the expedition team had accomplished remarkable feats, conquering new routes and making first ascents. With a series of successful climbs under their belts, the expedition could have concluded on a triumphant note. However, some members of the group harbored a different goal, one that would push them to their limits and test their mountaineering prowess even further.

The first ascent of Panch Chuli V

Among the expedition members, Stephen Venables, Victor Saunders, Richard Renshaw, and Stephen Sustad were particularly drawn to the unclimbed 6,437-meter peak of Panch Chuli V. Its remote location and challenging terrain presented an enticing challenge for these experienced mountaineers.

On June 17, accompanied by Chris Bonington, the four men set off up the Panch Chuli Glacier, carrying enough food for a four-day expedition. Their goal was clear: to conquer the elusive Panch Chuli V and add another remarkable achievement to their expedition’s record.

Venables vividly recalled their motivation for choosing Panch Chuli V: “We had chosen Panch Chuli V because it was the highest and most remote of the unclimbed peaks, a beautiful pyramid rising behind a barrier of icefalls.” The prospect of conquering this formidable peak ignited their passion for mountaineering.

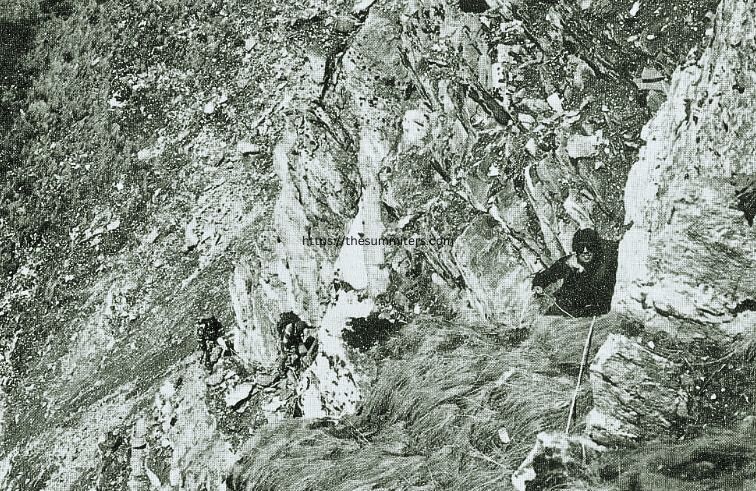

The team aimed to ascend the challenging south ridge, a route known for its complexity and danger. After successfully navigating the first two icefalls, they encountered a third icefall that proved to be too treacherous to pass directly. As snowfall began to intensify, they were forced to seek shelter at a col situated at an altitude of 5,400 meters.

The col, precariously positioned on a corniced crest, served as their temporary base camp. Above them, the buttress rose 200 meters, a formidable obstacle composed of steep rock, snow, and ice slopes. Their map indicated that the summit lay a kilometer beyond the top of the buttress.

Bonington, assessing the worsening weather conditions and the inherent risks of the remaining climb, decided to wait for the other three climbers at the precarious camp. Venables, Saunders, Sustad, and Renshaw, undeterred by the challenging conditions, pressed on towards the summit.

Sustad vividly recalled the upper section of the buttress, describing it as “some of the best and hardest mixed climbing he had ever experienced in the Himalaya.” The team’s determination and skill were put to the test as they tackled this formidable terrain.

On June 20, after days of persistent effort, Venables, Saunders, Sustad, and Renshaw finally reached the summit of Panch Chuli V. Their success marked a remarkable achievement, adding another conquered peak to the expedition’s impressive tally.

The accident

Having reached the summit of Panch Chuli V, the four-member team immediately began their descent, aware of the challenges that lay ahead. Chris Bonington, observing their progress from below, grew concerned about the slow pace of their descent, especially considering the technically demanding terrain and the looming threat of thunderstorms.

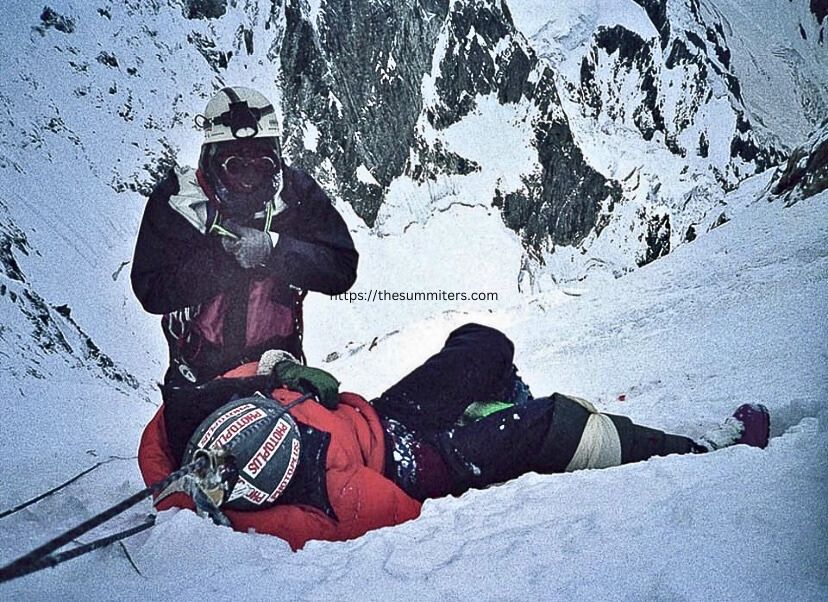

By 3:30 am, Sustad, Saunders, and Renshaw had completed their rappels, and Venables was in the process of removing the backup anchors, intending to use them later on the descent. At that moment, the piton he was relying on, driven into a horizontal crack in the rock, suddenly pulled out, sending Venables plummeting nearly 100 meters down the mountainside.

Venables recounted the terrifying fall in his own words, I think I had fallen about 20 feet when the noise started. It was a loud harsh, and violent sound. But it only slowly started on me that it was happening to me. It took a while for me to realize that my body was the one being subjected to this vicious beating being pounded and battered as I tumbled, bounced and flipped down the mountain.

His companions, witnessing the horrific fall, were convinced that this was the end for Venables. After the thunderous impact an eerie silence descended upon the mountain. However a few minutes later to their astonishment and relief they heard Venables voice calling out from a distance of 80 meters below.

A Difficult Rescue

Venables got really hurt—bad knee, broken ankle, chest injury. His team tried to help him down the mountain, but they needed a helicopter.

Kapadia and his friends were finishing their expedition stuff when someone rushed in. They found out Venables had an accident, so they went to organize a rescue. If they didn’t get a helicopter to them soon, things could go really bad.

Bonington was worried, wondering why this had to happen, especially at the end of the trip. He wished everyone was happily married like him.

The team waited for two days, hoping for a helicopter, but it couldn’t find Venables. So they made a backup plan: if the chopper didn’t show on the third day, they’d climb up with 20 people, a doctor, and everything they needed to bring him down safely.

Rescue at last

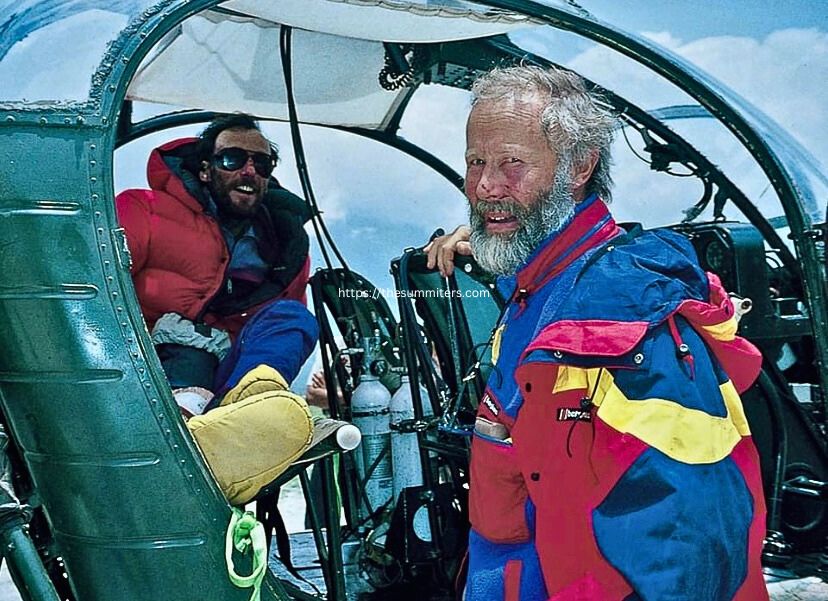

After four long days, the helicopter finally managed to rescue Venables. The pilots, P. Jaiswal and P.K. Sharma, did an incredible job. The other team members, Renshaw, Saunders, and Sustad, also made it back safely.

“It was a close call,” Bonington wrote. “All five of us were lucky to come back alive. But that’s the nature of climbing. Without that element of risk, very few Himalayan climbs would be possible. Despite everything, it was one of the best trips I’ve ever had in the mountains.”

We highly recommend reading the books written by the team about their experience on Pancha Chuli during that unforgettable summer of 1992

A Slender Thread Escaping Disaster in the Himalaya by Stephen Venables.

No Place to Fall Superalpinism in the High Himalaya by Victor Saunders.

Trekking and Climbing in The Indian Himalaya by Harish Kapadia.

2 comments

It’s appropriate time to make some plans for the

future and it’s time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I desire to suggest you some interesting things

or suggestions. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article.

I want to read more things about it!

Yeah Sure we will appreciate any Information regarding the article.