Introduction to Shishapangma

Shishapangma, towering at 8,027 meters (26,335 feet), is the 14th highest mountain in the world and one of the lesser-known giants of the Himalayas. Unlike many of its more famous neighbors, such as Everest and K2, Shishapangma is located entirely within Tibet, making it one of the few 8,000-meter peaks that lie wholly within a single country. This distinction has both added to its mystique and limited its early exploration, as Tibet remained largely closed to foreign climbers until the mid-20th century.

Name and Cultural Significance

The name “Shishapangma” comes from Tibetan, with the phrase “Shisha” meaning “grassy plain” and “Pangma” referring to a “high range or mountain.” Together, it roughly translates to “the crest above the grassy plains,” a reference to the fertile, high-altitude grasslands that surround the base of the mountain. This contrasts with the rugged, snowy peaks typical of the higher altitudes and emphasizes the unique environmental diversity of the region.

Shishapangma also has a lesser-known name, “Gosainthan,” which is derived from Sanskrit and means “the place of the saint” or “the holy abode.” This name reflects the cultural and spiritual significance of the Himalayas in both Tibetan and Hindu traditions, where many of the highest peaks are revered as sacred places, often associated with gods and saints. The mountain’s remote and unspoiled location has added to its aura as a mystical and challenging peak.

Significance in Mountaineering

While it may not carry the same fame as Everest or K2, Shishapangma holds a special place in the hearts of experienced mountaineers. It is often regarded as one of the “easier” 8,000-meter peaks, but this description is relative; any peak over 8,000 meters presents extreme challenges due to altitude, weather, and technical difficulties. In fact, Shishapangma’s remoteness, unpredictable weather patterns, and complex terrain make it a formidable goal for climbers.

One reason Shishapangma is less well-known is due to its location deep within Tibet, a region that was largely off-limits to Western explorers until the 1950s. Additionally, its prominence on the international mountaineering scene came later compared to other Himalayan giants. Despite its relatively late discovery, Shishapangma remains a popular target for climbers seeking to complete all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, often seen as a capstone achievement after tackling more technically demanding mountains.

Physical Characteristics and Surroundings

Shishapangma stands apart from other 8,000-meter peaks not only in its isolation but also in the unique geography of its surroundings. The mountain is part of the Langtang Himal range in the central Himalayas and sits on the Tibetan plateau, known for its expansive plains that gradually rise to meet towering peaks. From a distance, the mountain’s massive glaciers and snow-covered ridges dominate the skyline, forming a natural barrier between Tibet and the Langtang region of Nepal.

The northern side of the mountain, which is the most frequently climbed, features a series of large glaciers and gradual slopes that eventually lead to the steeper sections near the summit. This side of the mountain is often described as more approachable, with less technical climbing required compared to the more dramatic and dangerous southern face. The southern slopes of Shishapangma are steeper, with sharp rock faces and deep crevasses, making it far more challenging and only attempted by highly experienced climbers.

Isolation and Accessibility

Shishapangma’s location in the heart of Tibet also makes it one of the more remote peaks for climbers to reach. The nearest major city is Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, but most expeditions approach the mountain from the Tibetan-Nepalese border, usually traveling overland from Kathmandu. Even with the relatively easier access from modern road systems, reaching the mountain’s base camp can still take several days of travel through rugged, high-altitude terrain.

This remoteness means that climbers face additional challenges before they even begin their ascent. The lack of infrastructure and facilities in the region means that climbers must be largely self-sufficient, bringing all their supplies with them and relying on small Tibetan villages for basic necessities. While base camps for more popular peaks like Everest are bustling hubs of activity, Shishapangma’s base camp is much quieter, with fewer climbers and support staff.

Historical Significance and Late Exploration

Shishapangma was the last of the 14 8,000-meter peaks to be climbed, with its first ascent occurring in 1964 by a Chinese expedition led by Xu Jing. The relative isolation of Tibet and the political situation of the region delayed exploration, meaning Shishapangma had remained relatively untouched and unexamined for much of modern mountaineering history. Unlike Everest, which was the focus of numerous British expeditions throughout the early 20th century, Shishapangma didn’t attract much attention from Western climbers until China opened Tibet to foreign visitors after its annexation in the 1950s.

The successful 1964 ascent marked a turning point in the history of mountaineering, particularly for Chinese climbers, who had until then been overshadowed by Western expeditions in the Himalayas. Xu Jing’s team became national heroes in China, and the ascent helped to place Shishapangma on the global map of mountaineering, albeit somewhat later than other 8,000-meter peaks. Since then, the mountain has been climbed by climbers from around the world, though it still sees fewer ascents than peaks like Everest or K2 due to its remote location and challenging conditions.

Why Climbers are Drawn to Shishapangma

Shishapangma is particularly attractive to climbers seeking the experience of summiting an 8,000-meter peak without facing the overcrowding seen on Everest. The relative isolation, coupled with its reputation as one of the “easier” peaks, makes it a popular choice for climbers looking for a high-altitude challenge that doesn’t require the extreme technical skills of more dangerous mountains like Annapurna or Kangchenjunga.

However, despite its reputation as “easier,” Shishapangma has claimed the lives of many experienced climbers, and its weather conditions are notoriously unpredictable. The altitude alone presents a significant risk, as oxygen levels drop dramatically above 8,000 meters, and many climbers face the severe effects of altitude sickness. Like all 8,000-meter peaks, Shishapangma is located in what is known as the “death zone,” where the human body can no longer acclimatize and begins to deteriorate due to the lack of oxygen.

For those who are successful, however, summiting Shishapangma offers an unparalleled sense of accomplishment, along with stunning views of the Tibetan plateau, the Himalayas, and, on clear days, glimpses of Mount Everest to the south.

2. Geographical and Climatic Overview

Shishapangma is located in the central Himalayan range, in the heart of the Tibetan Plateau, which is often referred to as the “Roof of the World” due to its extreme elevation. Geographically, it dominates the southern edge of the Langtang National Park region, and its massif lies entirely within Tibet, making it one of the few 8,000-meter peaks situated wholly in one country. This section will explore the geographical features, landscape, and climatic conditions that define Shishapangma and make it such a formidable yet alluring peak for mountaineers.

Geographical Location and Surroundings

Shishapangma stands at 8,027 meters (26,335 feet) and is the 14th highest mountain in the world, yet it is considered relatively isolated compared to other Himalayan giants like Everest and K2. The peak is situated about 5 kilometers north of the Nepal-Tibet border and approximately 120 kilometers from Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital city. Though close to Nepal, Shishapangma is often approached from the Tibetan side due to easier access from the north.

The mountain is part of the Langtang Himal range, which runs along the border of Tibet and Nepal. The Langtang region is known for its rugged terrain, expansive glaciers, and high-altitude valleys. Shishapangma’s massif is characterized by its large, sweeping glaciers, sharp ridges, and towering ice-covered faces, creating a dramatic contrast against the plateau’s flatter areas at lower altitudes.

The proximity of the Tibetan Plateau plays a significant role in the mountain’s geography. The plateau, which is the largest and highest in the world, creates a unique environmental backdrop for Shishapangma. At an average altitude of about 4,500 meters (14,760 feet), the Tibetan Plateau is a vast, arid region that sharply rises into the towering peaks of the Himalayas. This elevation gives climbers a head start when approaching Shishapangma, as base camps are located at relatively high altitudes compared to those of other Himalayan mountains.

Physical Features and Topography

Shishapangma’s topography is diverse, with different challenges on each of its faces.

The North Face: The northern aspect of Shishapangma is the most frequently climbed route due to its less technical nature. The north side is primarily composed of large glaciers that gradually slope upwards, leading to ridges and ice fields that guide climbers toward the summit. The North Ridge is the most popular route, offering a comparatively straightforward climb (by 8,000-meter standards), but still requires crossing large crevasses, navigating icefalls, and contending with deep snow at higher altitudes.

The South Face: In stark contrast, the South Face of Shishapangma is one of the most challenging climbs in the Himalayas. It features steep rock walls, vertical ice sections, and extreme exposure to the elements. This face is regarded as a serious technical climb, reserved for only the most experienced alpinists. The Southwest Face in particular, is a sheer wall of rock and ice that requires advanced climbing techniques such as mixed climbing (rock and ice) and the ability to handle highly unstable weather conditions.

Summit Structure: Shishapangma has a distinctive summit structure with two significant points: the Central Summit at 8,008 meters and the Main Summit at 8,027 meters. Many climbers mistakenly reach the Central Summit, believing they have completed the climb, only to realize they need to traverse a narrow, technical ridge to reach the true Main Summit. This ridge is often considered treacherous, as it is exposed to high winds and is prone to avalanches.

At lower elevations, Shishapangma’s base is surrounded by broad, high-altitude plains, which are typical of the Tibetan Plateau. These plains are dotted with small lakes and rolling hills, giving the mountain a unique setting compared to other high-altitude peaks that rise abruptly from more rugged, forested valleys. The relative openness of the terrain around the base camp area allows for more straightforward access but offers little protection from the elements, especially the high winds common in the region.

Glaciers and Icefields

Shishapangma is heavily glaciated, with several large glaciers radiating from its summit. These glaciers, which flow down the mountain’s flanks, play a significant role in shaping the topography and influencing the difficulty of the climb.

The North-West Glacier: The most prominent glacier on Shishapangma is the North-West Glacier, which is part of the standard route used by most climbers attempting the summit. This glacier is a critical component of the ascent, providing a relatively gradual incline but also posing risks due to hidden crevasses and unstable snow bridges.

South-West Glaciers: On the southern and southwestern faces, the glaciers are far more rugged and broken up by rock faces and cliffs. These glaciers feed into a complex system of icefalls and seracs, making them some of the most dangerous sections for climbers. The terrain here is steep, and climbers must navigate areas prone to avalanches and falling ice.

Avalanche Risks: Due to the mountain’s glaciation, avalanches are a constant threat, particularly on the southern face, where the steeper terrain makes snow and ice more unstable. The combination of snow accumulation during the winter and rapid warming during the climbing seasons increases the likelihood of avalanches, which have claimed the lives of many climbers on Shishapangma.

Climatic Conditions

Shishapangma’s location deep within the Tibetan Plateau means that it experiences extreme and unpredictable weather conditions, typical of the high Himalayas. The climate on Shishapangma is characterized by strong winds, sub-zero temperatures, and rapidly changing weather patterns, making it a formidable challenge even for experienced climbers.

Monsoon Influence: Like much of the Himalayas, Shishapangma’s weather is heavily influenced by the Indian monsoon, which affects the region from June to August. During this period, heavy snowfall and poor visibility make climbing virtually impossible. The best climbing windows are during the pre-monsoon season (April-May) and the post-monsoon season (September-October), when the weather is relatively stable, and the skies are clearer.

Wind Patterns: Shishapangma is known for its strong winds, which can reach speeds of 100 km/h (62 mph) or more at higher elevations. The wind often picks up during the afternoon and can create dangerous conditions, especially near the summit, where climbers are exposed to the full force of the elements. Wind chill at the summit can drop temperatures to -30°C (-22°F) or lower, making frostbite a significant risk.

Temperatures: Even at base camp, which is located at an altitude of about 5,000 meters (16,400 feet), temperatures regularly drop below freezing, especially at night. At higher altitudes, particularly above 7,000 meters, temperatures plummet, making it one of the coldest climbs in the world. The high-altitude environment also means that the air is thin and dry, further complicating the ascent by increasing the risk of dehydration and altitude sickness.

Precipitation: The Tibetan Plateau is relatively arid compared to the southern slopes of the Himalayas, which receive heavy precipitation during the monsoon. However, Shishapangma still experiences significant snowfall, particularly in the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. This snowfall can create deep snowdrifts on the upper slopes, making progress slow and dangerous. The snow also makes crevasses on the glaciers difficult to see, adding to the hazards faced by climbers.

Environmental Conditions and Risks

The unique combination of geography and climate on Shishapangma creates a variety of environmental challenges for climbers.

Altitude and Acclimatization: The high-altitude environment presents one of the most significant challenges for climbers. At elevations above 8,000 meters, oxygen levels drop to around 30% of what is available at sea level. This extreme altitude creates a condition known as hypoxia, where the body is deprived of oxygen. Even experienced climbers struggle to acclimatize at these heights, and without proper acclimatization, climbers risk developing acute mountain sickness (AMS), high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), or high altitude cerebral edema (HACE)—all of which can be fatal if not treated quickly.

Weather Volatility: The weather on Shishapangma can change rapidly, and climbers often face white-out conditions, where visibility is reduced to near zero. Sudden storms can trap climbers high on the mountain, exposing them to the risk of frostbite, hypothermia, and exhaustion. The unpredictability of the weather means that climbers must be prepared for long periods of waiting at base camp for a clear weather window.

Summit Day Conditions: The final ascent to the summit is particularly exposed to the elements. The summit ridge is narrow, and strong winds can make it dangerous to proceed. Moreover, the extreme cold and lack of oxygen mean that climbers have limited time to reach the summit and descend before exhaustion or altitude sickness sets in. Climbers typically aim to reach the summit early in the day to avoid the worsening weather that often develops in the afternoon.

Accessibility and Terrain Approach

Shishapangma’s isolation adds to its allure for climbers who seek a more remote and less crowded experience compared to peaks like Everest. However, the remoteness of the mountain also adds logistical challenges. Most expeditions to Shishapangma begin in Kathmandu, Nepal, with climbers traveling overland to the Tibet border before making their way to Shishapangma’s base camp. The journey through Tibet passes through remote regions, often requiring days of travel across rough terrain before even reaching the mountain’s base.

The approach to base camp itself is less technical than on other 8,000-meter peaks, with rolling plains leading to the higher reaches of the mountain. However, the terrain becomes increasingly challenging as climbers ascend, particularly when they encounter the large glaciers and icefalls that dominate Shishapangma’s upper slopes.

3. History of Exploration

The exploration of Shishapangma, the 14th highest mountain in the world, is both a story of late discovery and intense determination, shaped by the geopolitical context of Tibet and the gradual opening of the Himalayas to mountaineers. As the last of the 8,000-meter peaks to be summited, Shishapangma’s exploration history is defined by the remoteness of its location, the delayed access to its slopes due to political restrictions, and the evolving nature of mountaineering technology and strategy over the decades.

Early Exploration and Geographical Recognition

The discovery of Shishapangma in the context of modern geography came much later than its more famous Himalayan counterparts. While mountains such as Everest, K2, and Kangchenjunga had been the focus of British expeditions and Western cartographers since the mid-19th century, Shishapangma remained largely unknown to the outside world. This was due to several factors, primarily the political isolation of Tibet and the region’s inaccessibility to outsiders.

Tibet was a closed-off region for much of the early 20th century, controlled by theocratic leaders and resistant to foreign influence. As a result, Shishapangma, despite its immense size, was not well documented in early geographic surveys of the Himalayas. Western expeditions and explorers focused their efforts on Nepal, India, and parts of China, with Tibet remaining a mysterious and largely forbidden land.

The mountain first appeared in Western maps in the early 20th century, but it was not given much attention due to its remote location and the political complexities of reaching Tibet. Early cartographers and surveyors only vaguely described the region, and Shishapangma remained a relatively obscure giant in the Himalayan landscape.

Tibet’s Political Landscape and the Opening of the Mountain

Tibet’s political status played a significant role in delaying exploration of Shishapangma. The Tibetan government, before China’s annexation of the region in the 1950s, had a longstanding policy of isolation, which included prohibiting foreign expeditions from entering its territory. This isolation meant that Shishapangma, like much of Tibet, remained untouched by the global mountaineering community during the early and mid-20th century.

The situation changed drastically in 1950 when the People’s Republic of China annexed Tibet. While this event was highly controversial and led to political upheaval, it also gradually opened Tibet to foreign climbers under the control of Chinese authorities. The annexation marked the beginning of China’s active interest in mountaineering and exploration, with the country using expeditions to demonstrate national prowess on the world stage.

By the early 1960s, the Chinese government began allowing controlled mountaineering expeditions in the Tibetan Himalayas, including those aimed at scaling Shishapangma. This shift in policy finally put the mountain within reach of climbers, though access was still tightly regulated and limited primarily to Chinese teams.

The First Ascent: 1964 Chinese Expedition

The first successful ascent of Shishapangma occurred on May 2, 1964, by a Chinese expedition led by Xu Jing, marking a historic moment in the annals of mountaineering. This achievement was significant for several reasons. Not only was it the last of the 14 8,000-meter peaks to be summited, but it was also a rare instance of a mountain of this stature being first conquered by a Chinese team rather than a Western or European expedition.

The 1964 Chinese expedition was heavily supported by the Chinese government, which viewed the climb as an important demonstration of national strength and self-sufficiency. The team was composed primarily of Chinese climbers, including some who had previously been involved in other significant Himalayan expeditions, such as the Chinese ascents of Everest from the northern (Tibetan) side in the 1950s.

The ascent itself followed the North Ridge route, which remains the standard route for climbers today. The team set up multiple camps at various elevations, slowly working their way up the glacier-covered slopes of the mountain. Their final push to the summit was successful, and they reached the top without significant mishap, a remarkable achievement given the limited mountaineering technology and logistical support available at the time compared to modern standards.

This ascent was a source of national pride for China, and Xu Jing and his team were celebrated as heroes. However, it took some time for the climb to gain international recognition, partly due to the isolation of China at the time and the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War, which limited direct communication between Chinese mountaineers and the global climbing community.

Opening to Foreign Climbers: The 1980s

For nearly two decades after the first ascent, Shishapangma remained largely closed to foreign climbers. However, in the early 1980s, the Chinese government began to relax its restrictions on foreign expeditions, partly due to the broader opening of China under the economic and diplomatic reforms of Deng Xiaoping. This new era of openness coincided with the growing interest in high-altitude mountaineering around the world, with more climbers seeking to complete the challenge of summiting all 14 8,000-meter peaks.

In 1981, Shishapangma was officially opened to foreign climbers, marking the beginning of its popularity as a destination for international mountaineering expeditions. The mountain’s north side was the most accessible, and it quickly became the preferred route for climbers from Europe, North America, and Asia.

The first foreign expedition to successfully summit Shishapangma was led by Doug Scott, a legendary British climber, in 1982. Scott’s team, composed of British climbers, made their ascent via the North Ridge, following the same route as the original Chinese expedition. Scott’s success helped to raise Shishapangma’s profile within the international climbing community, though it still remained less popular than other Himalayan peaks due to its remote location and challenging logistics.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Shishapangma continued to attract climbers from around the world, but it was never as crowded or commercialized as mountains like Everest or Cho Oyu. Its reputation as a quieter, more isolated 8,000-meter peak made it a preferred choice for experienced climbers seeking a more serene experience without the heavy traffic found on other mountains.

Notable Ascents and Tragedies

The history of Shishapangma is not without tragedy. Like all 8,000-meter peaks, it has claimed the lives of many climbers over the years, and some of the most famous names in mountaineering have faced significant challenges or even perished on its slopes.

1999 Tragedy: In October 1999, a notable tragedy struck when Alex Lowe, a renowned American climber, and David Bridges, a cinematographer, were killed in an avalanche while attempting to climb Shishapangma’s southern face. Lowe, considered one of the best alpinists of his generation, was scouting the mountain with Bridges and fellow climber Conrad Anker when they were caught in the avalanche. Anker survived the incident, but Lowe and Bridges were buried under tons of snow and ice. The loss of Alex Lowe sent shockwaves through the climbing community, and it took many years before his body was recovered, finally in 2016.

First Winter Ascent: Shishapangma was first successfully summited in winter on January 14, 2005, by a Polish climber, Piotr Morawski, and Italian alpinist Simone Moro. This achievement was particularly significant because winter ascents of 8,000-meter peaks are notoriously difficult due to the extreme cold, high winds, and reduced oxygen levels at such altitudes. Moro and Morawski’s ascent was hailed as a milestone in winter Himalayan mountaineering and demonstrated the peak’s enduring challenges even for the most experienced climbers.

Southwest Face Ascent: In 1987, Shishapangma’s treacherous Southwest Face saw its first successful ascent by Doug Scott and Alex MacIntyre, a remarkable feat given the steepness and technical difficulty of this route. The Southwest Face, often described as one of the most dangerous walls in the Himalayas, has since only been climbed by a few elite teams due to its steep rock and ice sections, constant risk of avalanches, and the extreme exposure climbers face.

Modern Expeditions and Current Status

In the 21st century, Shishapangma remains a sought-after peak for mountaineers, though it is less frequented than its higher counterparts, such as Everest or Lhotse. The mountain is popular with climbers looking to complete the 14-peak challenge, where mountaineers aim to climb all of the world’s 8,000-meter mountains.

However, Shishapangma’s reputation as one of the “easier” 8,000-meter peaks can be misleading. Despite being regarded as less technical on its northern routes, the mountain’s weather conditions, altitude, and remoteness continue to pose significant risks. The death zone above 8,000 meters, where the oxygen level is drastically reduced, makes the final push to the summit a grueling and life-threatening endeavor.

Geopolitical Considerations

Access to Shishapangma remains dependent on the political situation in Tibet and China. While foreign climbers can obtain permits to climb the mountain, Chinese authorities maintain strict control over the region, and expeditions must go through official channels. The political sensitivities surrounding Tibet, coupled with ongoing debates about the region’s autonomy, add a layer of complexity to climbing in this part of the Himalayas.

4. Shishapangma in the Context of the 8,000-meter Peaks

As the last of the 8,000-meter peaks to be summited, Shishapangma holds a unique place in mountaineering history. It symbolizes the end of an era when the world’s tallest mountains were being explored and climbed for the first time. Today, while it attracts fewer climbers than other peaks, it remains a mountain of immense beauty and challenge, standing as a testament to the enduring allure of the Himalayas.

The year-wise record of successful summits on Shishapangma showcases the evolution of mountaineering on this peak since its first ascent in 1964. Here is a detailed overview of some notable summits over the years:

1964: First Ascent

The first successful summit of Shishapangma occurred on May 2, 1964 by a Chinese-Tibetan expedition, led by Xu Jing. The 10-member team, including climbers such as Wang Fuzhou, Chen San, and Sonam Dorje, used the northern route, becoming the first to conquer this peak.

1980: Second Ascent

A significant gap followed the first ascent, with the second successful summit not taking place until 1980. A German team, led by Bernd Kullmann, climbed via the same northern route.

1981–1982: New Routes and Alpine Style Ascents

In 1981, Austrian climbers made a significant ascent via a variation of the northeast face. The following year, in 1982, British climbers Roger Baxter-Jones, Alex MacIntyre, and Doug Scott achieved the first alpine-style ascent via the technically challenging southwest face.

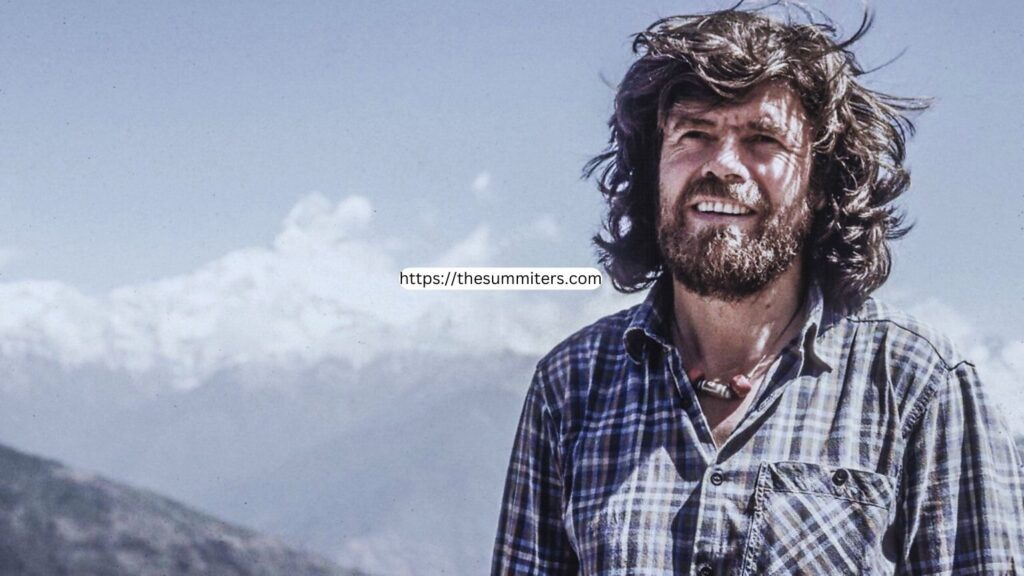

1987: First Solo Ascent

In 1987, the legendary Italian climber Reinhold Messner made the first solo ascent of Shishapangma, further establishing the mountain’s status in the world of extreme mountaineering.

1990s: Further Exploration and Tragedies

During the 1990s, Shishapangma saw a rise in international expeditions. Several summits were achieved, including attempts by well-known climbers like Carlos Carsolio from Mexico, who summited in 1990.

However, the decade also witnessed tragedies. Notably, in 1999, a deadly avalanche claimed the lives of renowned climbers Alex Lowe and David Bridges while scouting the southwest face for a ski descent.

2004: Ed Viesturs and the Controversy of Central vs. Main Summit

In 2004, American climber Ed Viesturs made headlines by returning to Shishapangma after his initial summit in 1993 was called into question. Viesturs had only reached the slightly lower central summit during his first attempt. On his return in 2004, he successfully reached the true main summit as part of his goal to climb all 14 eight-thousanders.

2011–2020: Continued Success

During the 2010s, numerous climbers successfully summited Shishapangma, including Naoki Ishikawa in 2014. In 2019, Mingma Gyalje Sherpa and Dawa Gyalje Sherpa added Shishapangma to their extensive list of eight-thousander summits. These achievements marked new milestones for Nepalese climbers in the high-altitude mountaineering community.

Recent Years (2021–2023)

Despite the challenges posed by political and environmental factors, Shishapangma remains a popular destination for elite climbers. In 2023, climbers like Nima Nuru Sherpa and teams from Imagine Nepal continued to achieve summits on the mountain, reinforcing its allure and prestige among the highest peaks in the world.

2023 – Deadly Avalanches

In October 2023, two tragic avalanches on Shishapangma claimed the lives of two American climbers, Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo, along with their Sherpa guides. Both women were experienced climbers aiming to complete all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. The avalanches occurred around 7,800 meters, and their deaths marked a somber close to the 2023 climbing season

2024 – Death of a US Climber

In October 2024, another tragedy struck Shishapangma, as a US climber died while attempting the ascent. The details surrounding this incident are still developing, but it highlights the ongoing risks climbers face on the mountain, despite its reputation as one of the “easier” 8,000-meter peaks

5. Climbing Routes and Difficulties

Shishapangma, standing at 8,027 meters (26,335 feet), offers several routes to its summit, each with varying levels of technical difficulty and exposure. The complexity of these routes is compounded by the mountain’s unpredictable weather, severe avalanche risks, and the high-altitude challenges that accompany any 8,000-meter peak. While it is often considered one of the more “approachable” of the 8,000ers, Shishapangma is by no means easy, and each route has its unique set of difficulties.

Northwest Face/North Ridge (Standard Route)

The most frequented path to Shishapangma’s summit is via the Northwest Face and North Ridge, which is often referred to as the “standard route.” This route is considered the least technical, making it a popular choice for commercial expeditions. The climb begins on the Tibetan Plateau, with an approach that leads to a series of glacier-covered ridges before reaching the summit ridge.

Technical Details

Climbing Type: Snow and ice route with some steep sections. The final ascent requires navigating a snowy ridge to reach the true summit.

Altitude Progression:

Climbers usually start their expedition from Base Camp at around 5,000 meters (16,404 feet), moving through Camp I at approximately 6,300 meters, Camp II at 7,100 meters, and Camp III (often called the high camp) at around 7,400 meters before attempting the summit push.

Key Challenges:

Glacial Travel: The route involves traversing large sections of glaciers, which present crevasse dangers, especially after fresh snowfall.

Summit Ridge Navigation:

Although not exceedingly technical, the summit ridge can be challenging due to snow conditions, winds, and steep exposure. The difference between reaching the central summit (around 8,008 meters) and the true main summit (8,027 meters) is significant; many climbers have mistakenly stopped at the central summit, especially in poor visibility.

Weather and Altitude:

The weather on the standard route can turn quickly. Climbers must be prepared for high winds and freezing conditions as they spend extended periods above 7,000 meters. As with all Himalayan climbs, the risk of altitude sickness increases the higher you go.

Advantages:

Relative Simplicity: While still a serious high-altitude climb, this route is less technical than many other 8,000-meter climbs, making it appealing for climbers with solid mountaineering skills but less technical experience.

Lower Objective Hazards: The north side of the mountain is less prone to avalanches and rockfall than the south face, making it safer, albeit still dangerous due to the inherent risks of altitude and crevasse crossings.

The Southwest Face

The Southwest Face of Shishapangma is one of the most challenging routes on the mountain. This face is steep and highly technical, involving mixed climbing on rock, ice, and snow. Only the most experienced and skilled climbers typically attempt this route, as it poses numerous objective dangers and requires advanced alpine techniques.

Technical Details

Climbing Type: The climb is a mix of rock and ice, with some sections involving steep rock walls and overhanging ice. The route includes ice fields, couloirs, and large seracs.

Technical Difficulty:

This route is classified as highly technical due to the sustained steepness and exposure. Climbers need to navigate through complex terrain, including vertical sections of ice and rock, which can be exhausting at high altitudes.

Key Challenges

Extreme Exposure:

The route is highly exposed, with long sections where climbers must navigate sheer cliffs and ice walls. This exposure, combined with the effects of high altitude, can make this route particularly exhausting and perilous.

Avalanche Risk:

The southwest face is notorious for its avalanche danger, especially after fresh snow or during periods of warming temperatures. Avalanches have claimed the lives of climbers on this face, making it one of the most dangerous aspects of the route.

Weather Vulnerability:

The southwest face is fully exposed to the elements, meaning climbers face extreme winds, unpredictable weather changes, and freezing temperatures. Storms can set in quickly, trapping climbers on the face.

Notable Ascents:

This face has seen some historic climbs, including a 1982 British expedition by Doug Scott and Alex MacIntyre, who completed the first alpine-style ascent via the Southwest Face.

The legendary Swiss mountaineer Ueli Steck made a solo speed ascent of the southwest face, showcasing the technical demands and high stakes of this route.

East Ridge

The East Ridge is a less-traveled but challenging route that requires technical climbing skills. Although not as demanding as the southwest face, the east ridge offers a steeper and more direct climb than the standard northwest route.

Technical Details:

Climbing Type:

This route involves climbing steep snowfields, mixed ice, and rock. The final portion of the climb follows a narrow ridge leading to the summit, with steep drop-offs on both sides.

Altitude:

The camps on this route are similar in altitude to those on the northwest route, but the climb is steeper, requiring greater physical effort.

Key Challenges:

Technical Ridge Climbing: The summit ridge is narrow and exposed, requiring precision and skill to navigate safely, especially in high winds.

Crevasses and Snow Conditions: The early sections involve crossing glaciers and snowfields that are prone to crevasses. Heavy snowfall can make the route unstable and increase avalanche risk.

Northeast Face

The Northeast Face is rarely climbed due to its technical challenges and high objective dangers. This route is steep, with sections of icefall, rock, and unstable snow conditions.

Technical Details

Climbing Type:

The Northeast Face offers mixed climbing on steep ice and rock. Climbers need to be skilled in both technical rock climbing and ice climbing.

Objective Dangers:

The face is highly prone to avalanches, making it one of the more dangerous routes on the mountain. Additionally, the icefall sections can be treacherous, with large crevasses and falling seracs posing serious threats.

General Climatic and Objective Hazards

Shishapangma is subject to extreme weather conditions typical of the Tibetan plateau. The peak is often lashed by violent winds, and storms can develop quickly, bringing whiteouts and avalanches. The narrow summit window typically falls in spring (May) and autumn (October), but even during these times, climbers face considerable risks from unpredictable weather patterns.

Avalanches

The risk of avalanches is particularly high on the more exposed faces, like the Southwest and Northeast faces. Avalanches have claimed the lives of numerous climbers over the years, including the tragic events of 2023, when twin avalanches took the lives of American climbers Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo(

Altitude:

At over 8,000 meters, the “death zone” is an ever-present danger. Prolonged exposure at high altitudes leads to increased risks of altitude sickness, which can be fatal without prompt descent. The thin air and limited oxygen also make every physical effort more demanding.

6. Famous Climbers and Expeditions on Shishapangma

Shishapangma, the lowest of the 14 8,000-meter peaks, has attracted some of the most renowned mountaineers in the world since its first ascent in 1964. While it may not carry the same global recognition as Everest or K2, Shishapangma’s challenging conditions, technical routes, and relative remoteness have made it a magnet for legendary climbers. Below, we delve into the history of some of the most famous expeditions and the mountaineers who have left their mark on this formidable peak.

First Ascent (1964) – Chinese Expedition

The first successful ascent of Shishapangma occurred on May 2, 1964, by a Chinese expedition led by Xu Jing. This was a significant achievement for China, as it was the only one of the 14 peaks over 8,000 meters located entirely within Chinese territory. The team consisted of several climbers, including Xu Jing and 10 others, who ascended via the North Ridge route.

Significance:

This climb was not only a historical first but also part of China’s growing mountaineering prowess. The route they pioneered, the North Ridge, is still the most popular route used by climbers today.

Challenges: The climb was undertaken during a time when Shishapangma’s true height was still a topic of debate. The team faced harsh weather conditions, limited resources, and the challenges of breaking new ground on a peak that was largely unknown to the international climbing community.

Reinhold Messner (1981) – Pioneering Central Summit Ascent

Reinhold Messner, one of the greatest climbers in history and the first person to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks, attempted Shishapangma in 1981. Messner ascended via the Southwest Face but did not reach the main summit. Instead, he reached the central summit (approximately 8,008 meters) due to poor weather conditions.

Significance:

Although Messner’s expedition did not reach the true summit, his ascent via the Southwest Face opened up new possibilities for more technically difficult routes on Shishapangma.

Legacy: Messner’s expedition helped raise the profile of the mountain among the international mountaineering community. His success, even without reaching the main summit, established the Southwest Face as one of the more challenging and respected routes.

Jean-Christophe Lafaille (2004) – Solo Attempt

Jean-Christophe Lafaille, a legendary French alpinist, attempted a solo ascent of Shishapangma in 2004. Lafaille had successfully summited Shishapangma previously, but during this solo attempt, he vanished without a trace.

Tragic Incident:

Lafaille disappeared in January 2006 after making an attempt on the summit during the winter season. The extreme cold and unpredictable weather conditions likely contributed to his demise, though his body was never found.

Significance:

Lafaille’s disappearance was one of the most high-profile mountaineering tragedies in recent memory. His attempt was emblematic of the risks of high-altitude solo climbing, especially on a peak like Shishapangma, which can be deceptively dangerous.

Ed Viesturs (1999) – American Success

Ed Viesturs, the first American to summit all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen, successfully summited Shishapangma in 1999. Viesturs is known for his cautious and calculated approach to high-altitude climbing, and his ascent of Shishapangma was no different.

Route:

Viesturs took the Northwest Ridge route and summited without the use of supplemental oxygen, a feat that highlights his stamina and experience at high altitudes.

Legacy:

Viesturs’ summit of Shishapangma was part of his broader quest to climb all of the 8,000-meter peaks, a goal he would complete in 2005 with Annapurna. His approach to climbing has been admired for its focus on safety and longevity in the sport.

Ueli Steck (2011) – Solo Speed Ascent

Ueli Steck, one of the most skilled and innovative climbers of his generation, made a solo speed ascent of Shishapangma’s South Face in 2011. Steck was known for his incredible speed and precision in high-altitude climbing, earning him the nickname “Swiss Machine.”

Route:

Steck’s ascent of the South Face was highly technical, involving a mix of rock, ice, and snow. His remarkable speed in climbing the face and his ability to do so solo earned him widespread admiration.

Significance:

This climb cemented Steck’s status as one of the greatest alpine climbers in history. His ability to move quickly and efficiently on technical terrain was unparalleled at the time, and his ascent of Shishapangma’s South Face became legendary.

Doug Scott and Alex MacIntyre (1982) – Alpine-Style First Ascent

In 1982, British climbers Doug Scott and Alex MacIntyre made the first alpine-style ascent of Shishapangma’s Southwest Face, a major achievement in high-altitude climbing.

Alpine Style:

Alpine-style climbing, which involves ascending a peak without the use of fixed ropes or established camps, was a significant departure from the siege-style expeditions common at the time. Scott and MacIntyre’s success on the difficult Southwest Face proved that large-scale expeditions were not always necessary for success on the world’s highest peaks.

Challenges:

This face is steep, highly technical, and exposed to avalanches and rockfall. The duo’s ability to navigate the treacherous terrain and reach the summit marked a turning point in how high-altitude climbs were approached.

Legacy: Scott and MacIntyre’s ascent was a breakthrough in modern mountaineering, inspiring future generations of climbers to adopt alpine-style techniques for tackling the world’s most difficult mountains.

2023 Avalanches – Tragedy Strikes

Shishapangma’s dangers were tragically underscored in 2023 when two avalanches claimed the lives of Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo, two American climbers attempting the ascent. Both were part of separate expeditions, but the avalanches occurred within hours of each other at around 7,800 meters, making it one of the deadliest days on Shishapangma in recent history.

Avalanche Risks:

Avalanches are a constant threat on the upper slopes of Shishapangma, especially after periods of heavy snowfall or temperature fluctuations. The 2023 incident highlighted the mountain’s volatility and the thin margin for error that climbers face.

Legacy:

The deaths of Gutu and Rzucidlo sent shockwaves through the mountaineering community, emphasizing the ever-present risks even for experienced climbers. Their tragic deaths came while they were attempting to complete the challenge of summiting all 14 8,000-meter peaks, which adds a deeper poignancy to their legacies.

October 2024 Tragedy – Mike Gardner’s Death on Jannu East

In October 2024, a tragic incident occurred not on Shishapangma but during an expedition on the North Face of Jannu East (7,468 meters) in Nepal, involving American climbers Sam Hennessey and Mike Gardner. While descending, Sam Hennessey reported that his climbing partner, Mike Gardner, had tragically fallen to his death.

The French climbing team of Benjamin Vedrines, Leo Billon, and Nicolas Jean were also on Jannu East at the time, attempting a new route. They encountered Hennessey during their descent after an urgent call for help from him. Hennessey explained that Gardner had fallen down the face of the mountain, a devastating loss.

Incident Details:

Vedrines recounted in an interview with French site Alpinemag how he noticed Sam waving at them while they were rappelling. Hennessey informed the French team that Gardner had fallen to the bottom of the face. Despite their best efforts to search for Gardner’s body at the base, they only found some of his clothing. The exact cause of the accident remains unclear at this time.

Mike Gardner:

Gardner was a second-generation mountain guide from Idaho and a highly skilled climber and skier. This was Hennessey’s third attempt on the North Face of Jannu East, and he had been awarded a prestigious American Alpine Club Cutting Edge Grant for this project. Gardner, who described himself as a climber, skier, and skateboarder, was a well-regarded figure in the mountaineering community.

This tragedy has further highlighted the dangers of high-altitude mountaineering and the risks involved, even for the most experienced climbers.

7. Controversies and Debates on Shishapangma

Despite its relatively lower profile compared to Everest or K2, Shishapangma has been the center of several controversies and debates over the years. These range from disputed summits, ethical concerns in mountaineering, the dangers associated with climbing 8,000-meter peaks, to debates over the true summit versus the central summit. Shishapangma’s relative isolation and lower traffic compared to other Himalayan giants have contributed to some unique issues, adding to the intrigue and complexity surrounding this 8,027-meter peak

Disputed Summits: True Summit vs. Central Summit

One of the most persistent controversies surrounding Shishapangma involves climbers who have mistakenly or intentionally stopped at the central summit (8,008 meters) instead of the true summit (8,027 meters). The mountain’s summit ridge is notoriously difficult to navigate, especially in poor weather conditions, and many climbers who reach the central summit believe they have summited the mountain. This has led to a number of disputed claims over the years.

Reinhold Messner’s 1981 Attempt

Messner, one of the greatest alpinists in history, only reached the central summit during his 1981 attempt due to bad weather conditions. While he did not claim the true summit, this set a precedent for future climbers who reached the central summit to mistakenly or inaccurately report success. Some climbers over the years have falsely claimed they reached the main summit when in fact they stopped short at the central point.

Verification Challenges:

Because Shishapangma does not see the same volume of climbers as other 8,000-meter peaks, verifying summits can be challenging. Historically, many summit claims have relied on personal accounts and photos, but the ridge between the central and true summits can be difficult to distinguish in photos due to angles and lighting. This has led to several disputed claims where climbers have thought they summited, only to later realize they had stopped at the lower central summit.

Importance of Clear Documentation: In recent years, with advancements in GPS technology and clearer photographic evidence, climbers are expected to provide accurate documentation of their summit attempts. This has reduced the number of disputed summits, but older claims remain a topic of debate in the mountaineering community.

8. Ethics of High-Altitude Rescue and Risk Management

Shishapangma, like many 8,000-meter peaks, has seen its share of ethical debates surrounding rescue efforts, particularly when it comes to the question of responsibility for fellow climbers in distress. The high altitude and extreme conditions on the mountain make rescue operations incredibly difficult, often putting the lives of rescuers at risk.

Jean-Christophe Lafaille’s Disappearance (2006): When Lafaille disappeared during a solo winter attempt on Shishapangma, questions arose about the risks of solo climbing at extreme altitudes. Solo climbing in the winter is one of the most dangerous forms of mountaineering, and Lafaille’s death sparked a debate about whether climbers should attempt such dangerous feats without support or backup.

2023 Avalanches

The 2023 avalanches that claimed the lives of Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo reignited the debate over risk management on high-altitude climbs. When these climbers were caught in avalanches at around 7,800 meters, rescue efforts were severely limited by the altitude and dangerous conditions. The question of when and how climbers should be rescued, and the ethical responsibility of fellow climbers and teams, came to the forefront of discussions within the mountaineering community.

Self-Reliance vs. Team Responsibility

In high-altitude climbing, there is often a fine balance between self-reliance and the responsibility to help others. Climbers on Shishapangma and other 8,000-meter peaks have faced ethical dilemmas when encountering distressed or incapacitated climbers. The difficulty of rescue at extreme altitudes, particularly in the “death zone” above 7,500 meters, means that climbers often have to make life-or-death decisions about whether to risk their own lives to help others.

9. Commercialization of Shishapangma

While Shishapangma has not seen the same level of commercialization as Everest, it has increasingly become a target for commercial expeditions. The mountain’s reputation as one of the “easier” 8,000-meter peaks has attracted a growing number of guided expeditions, some of which have raised concerns within the climbing community.

Safety Concerns

The commercialization of high-altitude climbing often brings less experienced climbers to dangerous environments. While Shishapangma is technically less demanding than peaks like K2 or Annapurna, its altitude and unpredictable weather make it a formidable challenge. Some critics argue that commercial expeditions can give climbers a false sense of security, leading to overcrowding and increased risk of accidents, as seen in 2023 with the avalanches that affected multiple climbing teams.

Impact on Local Communities and Environment

Like other 8,000-meter peaks, Shishapangma has faced issues related to environmental degradation due to increasing numbers of climbers. While the number of expeditions remains lower than on peaks like Everest, the environmental impact of climbers—particularly waste management—has become a growing concern. Additionally, the role of local Tibetan Sherpas and the exploitation of local labor in these dangerous environments has raised ethical questions about the fairness and sustainability of commercial expeditions.

10. Winter Ascents and the Race for Firsts

Winter ascents of 8,000-meter peaks are notoriously difficult and dangerous, and Shishapangma is no exception. Only a handful of climbers have attempted the mountain in winter, and those who have, faced extreme conditions that make the climb exponentially more challenging.

First Winter Ascent (2005)

The first winter ascent of Shishapangma was achieved on January 14, 2005, by Piotr Morawski and Simone Moro. This achievement came after several unsuccessful attempts by other teams. The debate around winter ascents often centers on whether such extreme challenges are worth the risk, especially given the limited weather windows and increased avalanche danger in winter conditions.

The Question of Motivation

Critics of winter ascents argue that the pursuit of firsts—whether it’s the first winter ascent, first solo ascent, or first alpine-style ascent—can sometimes cloud judgment and lead to unnecessarily risky behavior. The case of Jean-Christophe Lafaille’s fatal winter attempt in 2006 highlights the dangers of pushing the limits in pursuit of such achievements. These attempts often lead to difficult ethical questions when it comes to rescue operations, as seen in Lafaille’s disappearance.

Geopolitical and Access Issues

Shishapangma’s location entirely within the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China has historically posed challenges for climbers, especially during times of political tension. The mountain was closed to foreign climbers for many years after China’s annexation of Tibet in the 1950s, and even today, access to the region can be restricted due to political or environmental reasons.

Early Chinese Expeditions

The first ascent of Shishapangma was conducted by a Chinese expedition in 1964, during a period when China tightly controlled access to the region. This has led to a perception that Shishapangma was “off-limits” for many years, unlike other 8,000-meter peaks that saw earlier Western expeditions.

Tibetan Issues: Some climbers and human rights advocates have criticized expeditions to Shishapangma and other Tibetan peaks, arguing that climbing in Tibet under Chinese governance indirectly supports the political repression of the Tibetan people. While the mountain itself is a symbol of natural beauty and mountaineering achievement, its location in Tibet adds a layer of geopolitical complexity to expeditions.

11. Shishapangma Today

Shishapangma, the 14th highest mountain in the world, remains a significant destination for mountaineers, though it continues to be less frequented than its more famous Himalayan counterparts like Mount Everest or K2. The mountain, located entirely within Tibet, remains an enticing challenge due to its technical climbing routes, rapidly changing weather, and high-altitude hazards. In recent years, the mountain has continued to garner attention not only for its climbing achievements but also for the unfortunate tragedies that have occurred, underscoring the mountain’s enduring risk and appeal

Current Climbing Popularity and Accessibility

Shishapangma is less trafficked than other 8,000-meter peaks, partly due to its geographical location in Tibet and the complexities associated with obtaining climbing permits in China. Climbers must go through strict Chinese government procedures to access the mountain, which limits the number of expeditions compared to more accessible peaks in Nepal. Although some commercial expeditions offer guided climbs, they are fewer in number than those to Everest or Cho Oyu, which are more frequently attempted.

Recent Trends in Expedition Numbers

Fewer Expeditions Compared to Other 8,000ers: Shishapangma does not see the massive influx of climbers like Everest or Lhotse. One reason is that it is perceived as less glamorous or well-known, but also because of the logistical complexities involved in climbing in China.

Commercial Expeditions

Many commercial expeditions still use the North Ridge (Standard Route) because of its relatively lower technical difficulty. These trips often attract climbers who want to tick off another 8,000-meter peak but prefer a more straightforward ascent compared to the likes of K2 or Annapurna.

Alpine-Style Expeditions: In recent years, elite climbers have increasingly attempted the more difficult routes, such as the Southwest Face, using alpine-style techniques. These expeditions are typically smaller, lighter, and faster, avoiding the use of fixed ropes and pre-established camps.

Environmental Impact and Climate Change

As with many high-altitude environments, Shishapangma has not been immune to the effects of climate change. Melting glaciers, shifting snow patterns, and increased instability in the terrain have made climbing even more dangerous. Warmer temperatures have heightened avalanche risks, particularly on the steeper faces of the mountain.

Key Environmental Issues

Glacier Retreat:

Glacial recession has been observed in the Himalayan region, including around Shishapangma. This has impacted the routes that climbers take, altering the landscape and potentially making established paths more treacherous due to crevasses and icefalls.

Unstable Snowpack and Avalanches:

Changing snow conditions have increased the unpredictability of avalanches, especially on the more technical faces like the Southwest Face. Several deadly avalanches, including the tragic events of 2023, where two American climbers lost their lives, have been linked to these increasingly unstable conditions

Recent Tragedies and Safety Concerns

Shishapangma has seen a series of tragic incidents in recent years that underscore the mountain’s inherent dangers. The unpredictable weather, high-altitude challenges, and objective hazards like avalanches and rockfall have led to the deaths of several prominent climbers.

Notable Incidents

2023 Avalanches:

In October 2023, two American climbers, Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo, were killed in separate avalanches on the mountain. These incidents occurred just hours apart as the climbers neared the summit, emphasizing the avalanche risk at high altitudes

2024 Fatality:

In October 2024, American climber Mike Gardner died in a tragic fall during an expedition on Jannu East, another Himalayan peak, while his climbing partner Sam Hennessey survived. Gardner’s death, although not on Shishapangma itself, highlights the ongoing dangers climbers face in the broader Himalayan region

Technological Advancements in Climbing

The climbing community has seen significant advances in gear and technology, making high-altitude expeditions like those to Shishapangma theoretically safer, but the inherent dangers remain.

Innovations

Better Gear and Equipment:

Modern climbers have access to highly technical clothing, climbing gear, and navigation systems that were unavailable to early Shishapangma pioneers. Lightweight yet durable equipment, including improved crampons, ice axes, and climbing harnesses, enables climbers to move faster and more safely through challenging terrain.

Weather Forecasting:

One of the biggest advancements has been in meteorology. Climbers now benefit from accurate weather forecasts that allow them to better time their summit attempts, reducing their exposure to sudden storms or avalanches. However, these tools are not foolproof, as evidenced by the tragic events of 2023.

The Mountain’s Role in the 8,000er Challenge

For those attempting to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, Shishapangma often serves as either an early step due to its reputation as “one of the easier 8,000ers or as a later objective for those who have already experienced on more difficult peaks. Its altitude, while still significant, is lower than other Himalayan giants, making it an important goal but sometimes considered a less technically demanding peak.

A Step in the 8,000ers Quest

Climbers’ Perspectives:

For climbers looking to tick off all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, Shishapangma remains a vital objective. While many summits, particularly via the North Ridge, are achievable for experienced climbers, the technical challenges of other routes like the Southwest Face still demand significant expertise.

Success Rates:

The success rate on Shishapangma is generally higher than on some of the other, more dangerous 8,000ers. The standard route, in particular, sees more frequent successful summits, although these often stop at the central summit rather than the true summit, which has sparked debate over what constitutes a complete ascent.

Future Prospects and Challenges

As climbing technology continues to evolve and more climbers gain access to high-altitude environments, Shishapangma will likely remain a key destination for both professional and amateur climbers. However, the mountain also faces significant environmental, political, and logistical challenges that will shape its future.

Key Challenges

Environmental Concerns:

As global warming intensifies, the region’s glaciers and snowfields may become even more unstable, increasing the dangers for future expeditions. The changing landscape could alter traditional climbing routes and create new hazards.

Access and Permits:

Climbing in Tibet remains highly regulated by the Chinese government, and shifts in the political landscape could either restrict or ease access to Shishapangma. Climbers currently must navigate complex bureaucratic processes to obtain permits, which may impact future expeditions.

Conclusion

Shishapangma today stands as a significant yet dangerous destination for mountaineers. While it may not see the same number of climbers as other 8,000-meter peaks, its technical challenges, environmental risks, and ongoing appeal as a key summit in the 8,000-meter club ensure that it will continue to draw climbers from around the world. As the impacts of climate change, evolving technology, and logistical complexities continue to shape the landscape of high-altitude mountaineering, Shishapangma remains an important and revered objective in the climbing community.