In spring 2024, the climbing season on Annapurna was unusually brief. After setting up ropes to Camp 3 during the first window of good weather, climbers had to make a tough choice: either summit or return home. Once the initial group reached the top and descended, all the expedition teams swiftly packed up and departed from the mountain.

To the disappointment of many, some climbers didn’t even stick around to savor their accomplishment at Base Camp. Instead, they opted to be airlifted straight from Camp 3 back to Kathmandu by helicopter.

Two Weeks on Annapurna: A Race Against Time

In late March, the first climbers arrived at Base Camp. They squeezed in one trip to Camps 1 and 2 before the weather took a nasty turn. Almost everyone decided to retreat to Pokhara for a few days of rest. Meanwhile, the sherpas hustled to set up Camp 3 and lay ropes for Camp 4. When the skies cleared, they all made another dash for the summit.

For those who arrived later at Base Camp, there wasn’t even enough time for a full trip up. They were disappointed to learn that there wouldn’t be any more chances to reach the top.

David Nosas, hailing from Spain, shared his experience, “I had to work until the end of Easter, so I didn’t have much time to acclimatize. We ended up spending a total of nine days on the mountain!”

Despite the tight schedule, Nosas and his partner, Domi Trastoy, supported by Satori Expeditions, decided to make an attempt for the summit on April 13. Nosas had to turn back at 7,400 meters, but Trastoy, using supplementary oxygen, pushed on and reached the top at 7,500 meters.

Flor Cuenca, a Peruvian residing in Germany, explained her unexpected journey, “My plan was to fly to Nepal, then to Pokhara, and finally to Base Camp. But my acclimatization round turned into a sudden summit attempt.”

Using a Helicopter at Camp 3

Just like in her previous climbs, Cuenca was self-reliant, carrying her own tent and supplies without using oxygen or sherpa support. Once on the mountain, her aim was to swiftly reach Camp 3. Her plan was to set up her tent as high up as possible and then return later for the final push to the summit.

However, a snag arose. Mikel Sherpa, assisting Australian climber Allie Pepper, suggested they follow the team fixing ropes to the summit. But Cuenca had forgotten her warm down suit back at Base Camp!

Luckily, Mikel came up with a solution. He arranged for Cuenca’s down suit and warm gloves to be airlifted in a helicopter heading to the higher camps. This enabled Cuenca to reach the summit the following day.

But why was there a helicopter flying to Camp 3 on Annapurna in the first place?

April 12: A Tough Day to Summit

Summiting Annapurna is always demanding, but April 12 proved to be exceptionally challenging. The sherpas had only managed to secure ropes up to Camp 4. Two groups had set off for the summit the previous night: one led by Seven Summit Treks, which included Nepalese rope fixers, and Irina Galay from Ukraine, supported by Mingma Dorchi Sherpa from Pioneer Adventure.

It’s worth noting that the climbers were already exhausted upon reaching Camp 3. They had just completed the most dangerous and physically taxing part of the Annapurna climb.

Samiur Rashid from the UK shared with ExplorersWeb, “I summited Everest in 2023, and Annapurna is much, much tougher. Despite considering myself quite fit, Annapurna drained all my strength. Some vertical sections seemed impossible to conquer. It was an incredibly challenging climb.”

Irina Galay recounted her experience to ExplorersWeb, saying, “We reached Camp 3, took a short rest, and began our ascent at 6:30 pm on April 11. By 8:00 pm, we had reached Camp 4 and noticed another team already setting out to secure the ropes. After a brief break, we followed their lead.”

Galay, who had to rely on bottled oxygen from Camp 3 onwards, mentioned that fresh snow had made the upper sections more difficult to navigate. “The journey to Annapurna‘s summit is extremely long, and waiting, sometimes for over an hour as the rope fixers did their work, only added to the challenge.”

Frostbite: A Chilling Experience

“That’s when I reckon the frostbite started setting in,” Rashid mused. “When you’re on the move, you feel the cold, but your blood keeps circulating. But all that stopping and waiting, it just numbed our limbs.”

Galay recalled vividly, “After nine grueling hours, we had only reached 7,300 meters, and the cold was biting. I saw people trying to pass each other, but it seemed pointless because we were all stuck in the same spot. Some were eager to be at the front, while others had different agendas. Sherpas were urging their clients ahead with short leashes. I realized standing idle made no sense. So, I pushed forward to the fixing team and pitched in to help.”

The Section without Ropes

Galay elaborated, “As I followed them, they began veering to the right, and there was no rope. Despite the lack of rope, the snow conditions were manageable, allowing us to proceed cautiously with the help of ice axes. It was risky, but scaling Annapurna always involves risks.”

Galay explained that it took the group approximately 40 minutes to traverse this section without ropes.

Upon reaching the summit, Galay found herself right behind two rope fixers and two other Nepalese climbers.

“They asked me to wait a moment while they secured everything,” she recounted. “Then they permitted me to approach. They fastened my backpack to the station with a carabiner, and I settled in. Following behind me was an 18-year-old climber, Nima Rinji Sherpa, who was climbing without oxygen and yet managed to keep up with me. He displayed remarkable strength! I attempted to let him go ahead, but he insisted, ‘No, no, you go first, you deserve it.’ He was the next one to reach the summit after me.”

Nima Rinji was actually only 17 when he summited Annapurna and is on track to become the youngest person ever to summit all 14 of the world’s 8000 meter peaks. Annapurna marked his 11th summit. He’s vying for this record against slightly older climbers like Shehroze Kashif from Pakistan and Adrianna Brownlee from the UK.

In addition to Galay and Dorchi Sherpa, the summiters that day, as reported by Seven Summit Treks, included Chhang Dawa Sherpa (the expedition leader), the young Nima Rinji Sherpa (without oxygen), Pasang Nurbu Sherpa, Ngima Tashi Sherpa, Mingtemba Sherpa, Pasang Sherpa, Pemba Thenduk Sherpa, Lakpa Temba Sherpa, and Manish Maharjan. Among the international climbers were Klara Kolouchova from the Czech Republic, Iryna Karagan from Ukraine, and Samiur Rashid from the UK.

A Close Call on the Way Down

Galay mentioned she spent roughly an hour at the summit before beginning her descent. She carefully made her way through the section without ropes.

“While I was descending, I spotted some sherpas helping a climber who seemed to be in a bad way,” Galay recounted. “It wasn’t until later that I found out it was Pavel, another Ukrainian climber.”

Sydorenko didn’t manage to reach the summit. He collapsed while climbing up, just above Camp 4.

“I’m not sure if his sherpa was with him, but he lay on the ground for quite some time,” Rashid remembered.

Eventually, sherpas who were coming down from the summit stopped to help him. Klara Kolouchova found him around 6 pm, about 200 meters above Camp 4, as she descended from the summit.

A Ukrainian Climber’s Near-Death Experience

Kolouchova recounted the incident

He was being lowered on a rope by three sherpas one of whom was my sherpa, Chhepal. When I arrived at the scene, Pavlo was barely responsive, if at all. He couldn’t move and simply gestured to his chest indicating he was struggling to breathe. Fortunately I had an emergency adrenaline pen, which I administered into his thigh.

After a while, he managed to stand with assistance, and slowly made his way towards Camp 4. I made sure he was securely tethered to another sherpa with a short rope before continuing my descent to Camp 4.

Once there, I consulted with Allie Pepper, who was preparing for her summit attempt at Camp 4. We agreed to administer a shot of dexamethasone to Pavlo as soon as he arrived. With that settled, I proceeded down to Camp 3 for the night.

The following morning, a helicopter rescue evacuated Pavlo and Iryna [Karagan] back to Base Camp. I firmly believe that the timely administration of adrenaline, coupled with the dexamethasone, saved his life.”

Both Kolouchova and Rashid attested to Iryna Karagan’s extreme exhaustion and the extensive support she required during the descent.

“I don’t believe there was any competition between the two Ukrainian climbers, Irina Galay and Iryna Karagan, to reach the summit first. It was evident that one was much stronger than the other,” Rashid observed. “Having climbed with Galay for most of the journey, I can attest to her remarkable strength and skill.”

Galay and Mingma Dorchi reached Camp 3 around 6 pm, just as darkness descended, and settled in for the night.

From Camp 3 to Base Camp — or to Kathmandu

When we asked Irina Galay about her experience the morning after the summit (April 13), here’s what she shared:

“When I woke up at Camp 3 after reaching the summit, I noticed many people at Camp 3 were getting ready to be airlifted by helicopter. One of them was Iryna Karagan. I advised her against it because the most crucial part of the route is between Camp 2 and Camp 3. If someone can’t manage that part, I don’t think they should consider the summit complete. But she insisted she felt very unwell and wanted to be with Pavel. Another Nepali from Camp 3 also left by helicopter.”

Kolouchova and Rashid confirmed that Karagan boarded the helicopter and departed. They couldn’t determine if she was too exhausted to continue descending. Kolouchova mentioned that Karagan appeared worn out but not necessarily sick.

“It’s amazing how much more the human body can endure when we think we’ve reached our limit,” Rashid commented. “Even I wasn’t feeling my best on the descent, and I was offered a helicopter ride as well. However, I vehemently refused.”

Rashid was resolute in his decision. “I’d prefer to risk my life than take a helicopter,” he told his sherpa. “I am unwavering on this point — a legitimate climb starts and ends at Base Camp, no exceptions,” he emphasized. “I convey this to every climber. Reaching the summit with part of the journey completed by helicopter isn’t a true summit.”

Both Rashid and Galay mentioned that some Nepalese climbers were also airlifted, but they couldn’t recall who they were. We reached out to Seven Summit Treks’ PR representative to inquire if any team members were airlifted from Camp 3. We’re awaiting their response.

ExplorersWeb has also reached out to Iryna Karagan and Allie Pepper for their perspectives. On April 13, Pepper was preparing for her summit attempt. We’re still awaiting their replies.

Rescue or Shortcut?

Last year, a significant number of climbers faced evacuation from the high camps of Annapurna. Urgent rescues, such as Jonathan Lamy’s frostbite and Baljeet Kaur’s two-day ordeal at high altitude, were among them. Tragically, Noel Hanna lost his life, and five others – Arjun Vajpai, Naila Kiani, Shehroze Kashif, Dawa Nurbu Sherpa, and Lakpa Sherpa – had to be airlifted from Camp 3 due to hazardous conditions below. These evacuations ignited a contentious debate about the validity of such summits for the climbers’ 14×8,000-meter peak lists.

Expedition leaders spared no effort in ensuring the safe descent of sick or injured climbers. The crux of the debate lies not in the decision to airlift, but rather in its impact on a climber’s claim of summiting.

If the evacuation is prompted by an imminent risk, it becomes a personal choice and should be left to the climber, provided they are transparent about it. However, many argue that such climbs should be considered incomplete, akin to retreating due to perilous mountain conditions. Conversely, if the evacuation aims solely to bypass potential risks and expedite the return to Base Camp or town, some contend that the climb lacks integrity and falls short of mountaineering ethics.

A Common Practice

Surprisingly, airlifts have become a regular occurrence for those who are willing to use them and can afford it. This trend was observed by Rashid during his time on Everest in 2023.

“Climbers opt for helicopter rides from Camp 2 when they feel exhausted and want to avoid the dangers of the Khumbu Icefall,” he explained. Some even choose to start their summit attempt from there.

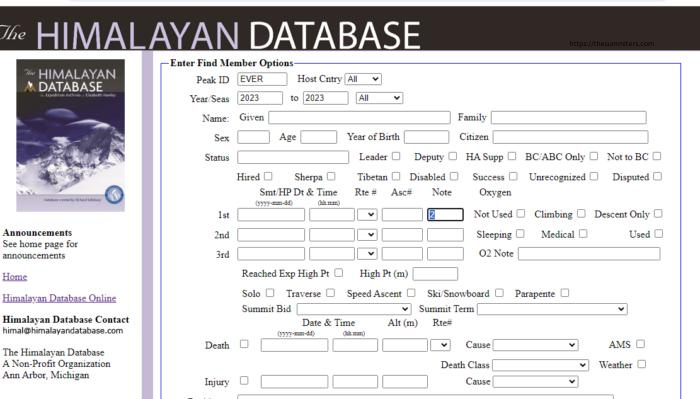

According to The Himalayan Database, a staggering 23 climbers received aviation assistance last year while descending from points above Base Camp on Everest. You can verify this information yourself by visiting The Himalayan Database online and using the search function under ‘find members.’ Simply input the peak ID, the season, and type ‘2’ in the ‘note’ box: 1 = Flight-assisted ascent above BC; 2 = Flight-assisted descent above BC; 3 = Flight-assisted ascent & descent above BC. Special thanks to Billi Bierling and The Himalayan Database team for providing these instructions!

“Honestly, it’s puzzling to me because climbing is about completing the entire journey, both up and down,” remarked Irina Galay. “If you’re able to descend safely, you do so. If not, it’s a rescue or evacuation. Anything else seems absurd and requires regulation.”

At ExplorersWeb, we firmly believe that taking a helicopter shortcut is unacceptable for any summit record. However, it’s a reality that Nepalese authorities regularly validate such summits.

We reached out to both The Himalayan Database and 8000ers.com for their perspective on this matter.

The Debate Heats Up: Helicopter Assisted Summits and Climbing Records

Mountain climbing record keepers are facing a growing dilemma, how to handle summits achieved with aviation assistance in the meaning climbers who use helicopters to reach higher camps. While some argue that such climbs distract from the true spirit of mountaineering others see them as a practical option in today’s fast paced climbing world.

The current system presents challenges. Information on helicopter use is often scarce, as climbers aren’t obligated to report it. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to distinguish between an “assisted” and a traditional climb.

To address this issue, Eberhard Jurgalski, a prominent record-keeper, plans to incorporate details on helicopter use into his upcoming, expanded summit lists. This data will be alongside other factors like reliance on supplemental oxygen, fixed ropes, Sherpa support, and pre-established camps.

The central question remains: Does a helicopter ride during a climb diminish the accomplishment of reaching the summit? Jurgalski believes it only truly matters when climbers are attempting to break or set records. In those cases, a helicopter-assisted summit wouldn’t be considered valid.

Modern climbing trends also play a role. Many climbers now tackle multiple high peaks aiming to conquer all 14 mountains exceeding 8,000 meters. Helicopters can be a valuable tool to achieve this ambitious goal. Similarly, Sherpa guides view summiting mountains as a way to build their resumes and experience.

The debate surrounding helicopter use in mountaineering is sure to continue. As Jurgalski’s new system goes into effect, it will shed light on the evolving landscape of summit attempts and offer climbers and record-keepers a clearer picture of how each peak is conquered.

The Descent’s Grip: Fear and Frustration

Ascending a mountain, the summit consumes your thoughts. Everything else fades into the background, replaced by the singular goal of reaching the peak. Maya Galay, however, describes a stark shift in mentality during the descent. Her focus narrows entirely to returning safely, her thoughts turning to the loved ones waiting below.

The treacherous section between Camps 3 and 2 underscores the dangers climbers face. Galay paints a vivid picture of this particularly terrifying area, prone to avalanches every 20 minutes. She recounts witnessing and hearing these avalanches firsthand, the experience leaving her shaken to her core. Despite the overwhelming fear, she persevered, pushing on while others opted for helicopter evacuation.

This disparity in descent methods fuels Galay’s frustration. She questions the fairness of awarding the same certificates to those who descend on foot, battling their fears, and those who choose the relative safety of a helicopter ride. In her eyes, the method of descent becomes a reflection of a climber’s commitment and courage, and the current system feels like a disservice to those who face the full challenge.

Galay’s account sheds light on the emotional rollercoaster of a mountain descent, particularly when faced with extreme danger. It also highlights the debate surrounding the recognition climbers receive, and the potential need for a more nuanced system that acknowledges the varying degrees of risk undertaken.

Walking Down’s Cost: A Summit Achieved, Dreams on Hold

Samiur Rashid’s decision to descend the mountain under his own power came at a significant cost. Reaching Base Camp, he discovered his toes had succumbed to frostbite, a painful condition caused by extreme cold. This unexpected setback shattered his ambitious plans for the climbing season.

“I had a lot lined up,” Rashid confided. There were other peaks in Nepal I wanted to conquer, and then I was headed to Pakistan. Unfortunately that’s all on hold now. His frostbitten right foot demands a lengthy recovery, forcing him back to his home in London instead of scaling new heights.

Reflecting on his choice at Camp 3, Rashid admits he wasn’t aware of the frostbite when the helicopter evacuation was offered. He ponders what he might have done with that knowledge. “Even knowing about the frostbite, I would have tried to treat my feet, wrapping them up and warming them as best I could. Then, I would have continued the descent on foot with my Sherpa.” His determination to walk down, despite the potential consequences, speaks volumes about his commitment to facing the mountain’s challenges head-on.

A Shadow Over the Summit: Transparency and the Future of High-Altitude Climbing

A dark cloud hangs over Himalayan mountaineering reflecting the challenges faced by the sport in recent years. Unprincipled practices by a small minority of climbers and outfitters are informal the reputation of the entire community. This culture of secrecy, often perpetuated by a code of silence among outfitters and clients, only exacerbates the problem. Climbers who adhere to a strict ethical code find it disheartening to see their hard-earned achievements compared to those attained through “mechanized shortcuts” like helicopter use.

The pressure to maintain good relationships with outfitters and fellow climbers often discourages whistleblowing. However, this silence inevitably leads to the truth surfacing, further eroding the credibility of the entire industry.

German climber Norrdine Nouar serves as a beacon of ethical conduct. In April 14th’s summit of Annapurna, he eschewed both bottled oxygen and personal Sherpa support, relying solely on his own skill and acclimatization achieved through repeated ascents of Thorong La. While acknowledging that self-sufficient, oxygen-free climbers may not be the most lucrative clientele for expedition companies, Nouar expresses deep concern about the state of high-altitude mountaineering.

“We’ve reached a critical juncture,” Nouar emphasizes. “The image and reputation of 8,000-meter climbing is in a terrible state.” He compels climbers to confront fundamental questions about their motivations: “Why climb a particular mountain? Is it driven by a love for the challenge and the mountain itself, or by the allure of an easy summit, a trophy picture, and bragging rights?”

The public perception of Everest climbers, Nouar laments, has devolved into a caricature: “A bunch of idiotic rich egos who want to buy their way to the top with an excessive reliance on Sherpas.” These are harsh realities, but Nouar believes confronting them head-on is essential. The future of mountaineering hinges on the willingness of climbers to embrace transparency and establish clear distinctions between climbing styles.

Taking a helicopter to a higher camp is a personal choice. However, Nouar argues, concealing this fact while claiming a summit achieved with a different set of rules undermines the spirit of the sport. The path forward lies in fostering a culture of honesty and open communication within the climbing community.